Thousands of people come to Ventura each year and end up visiting the Mission.

by Randal Beeman

In 1816, Mission San Buenaventura appeared to be a thriving entity, with nearly 40,000 head of livestock, ample stocks of grain, and a population of over 1,300 mostly native people. Mission San Buenaventura had already survived fires, earthquakes, and a major tsunami. Soon the threat of pirates and outside invaders would worry the locals.

The local Chumash culture that had developed into a fascinating and economically sustainable society over thousands of years experienced extreme distress. With the arrival of the Spanish, the native people of Ventura endured a spiritual and biological attack that nearly wiped them from the face of earth.

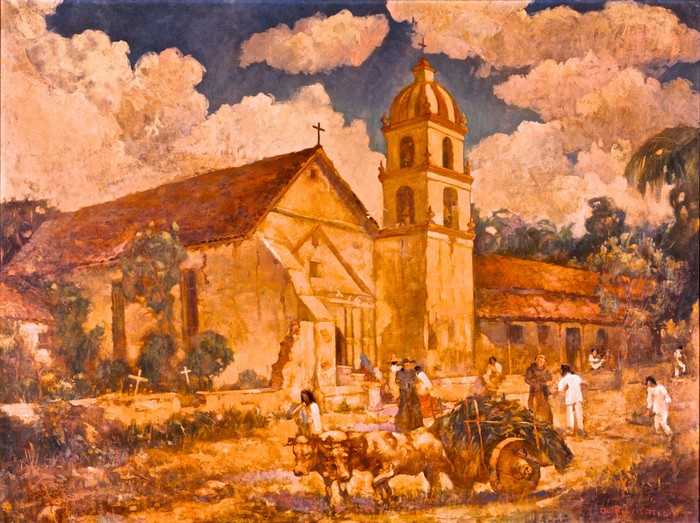

While most Californians enter a Mission at least once in their lives, and a Mission visit is mandatory for tourists, the version of history that tourists and schoolchildren have digested over the decades neglects the people that actually built the Missions. Like the history, the actual Missions the public see today are for the most part white-washed facsimiles of the real thing, “havens of happiness…places of song, laughter, good food, beautiful language and mystical adoration of the Christ” in the words of one observer.

The Missions were rebuilt not by the Catholic Church, but rather they served as a motif for real estate boosters that fed into a romanticized identity for California and a perfect pitch to tourists. Today when you visit a Mission, the bookstore usually has a copy of Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona, the 1884 political-romance novel set in the California Missions that, more than anything else, led to the Mission revival.

Santa Barbara bought into the Mission theme more completely than Ventura, but you can look not only across California to see the architectural influence of the Mission Revival, but there are even skyscrapers in Manhattan claiming the Mission motif.

Of course, boosters, tourists, and the publishers of coffee table books haven’t shown much interest in depicting the Mission experience for what it really was – a horrific and often brutal chapter in human history.

By most measures the Mission system was a failure. The handful of priests the Spanish sent to California could not baptize natives fast enough to keep up with the appalling death rate from the diseases brought from Europe. The force that kept the Missions in place – soldiers – were notorious for raping native women and setting off periodic rebellions that plagued the Missions from the onset to the end.

Native people had their children taken away, their cultures assaulted, and they were routinely whipped and pressed into forced labor. When the “liberal” Mexican ranchers in California set the neophytes free during the process called secularization in the 1830s, they conveniently took all the property the natives had developed.

The recent elevation of Father Junipero Serra to the status of Sainthood in the Catholic Church has resurrected discussion of the legacy of the Missions. To its credit, the Catholic Church has embraced a new look on how the history of the Missions should be revised.

A visit to the web page of the Mission San Buenaventura includes an invitation to the public to join in the conversation of the Mission history and a promise to “more accurately present history, the perspective of the California Indians and the Mission’s impact on Indian life. “Nonetheless, many native people and organizations have continued to oppose the canonization of Father Serra, the “founder” of Ventura whose statue gazes down from City Hall as an arbiter of authority and justice.

Thousands of people come to Ventura each year and end up at the Mission, which is also a functioning Catholic community. Perhaps a visit to the Mission is in order to connect to the local Native American presence and to witness the change, or lack thereof, in how the Mission history is interpreted.