∙ SPAN Thrift Store is open to the public and looking for donations of adult clothing, household items and tools if you’ve got items you no longer use. SPAN Thrift Store regularly provides $10 spays and neuters for low income households with cats and dogs.

∙ SPAN Thrift Store is open to the public and looking for donations of adult clothing, household items and tools if you’ve got items you no longer use. SPAN Thrift Store regularly provides $10 spays and neuters for low income households with cats and dogs.

Three upcoming clinics are: Tuesday, November 2nd at Shiells Park, in the parking lot, located at 649 C St., Fillmore, a second clinic on Tuesday, November 9th at SPAN Thrift Store parking lot 110 N. Olive St. (behind Vons on Main), and a third clinic at the Albert H. Soliz Library – El Rio, 2820 Jourdan St., Oxnard on Tuesday, November 16th.

Please call to schedule an appointment (805) 584-3823.

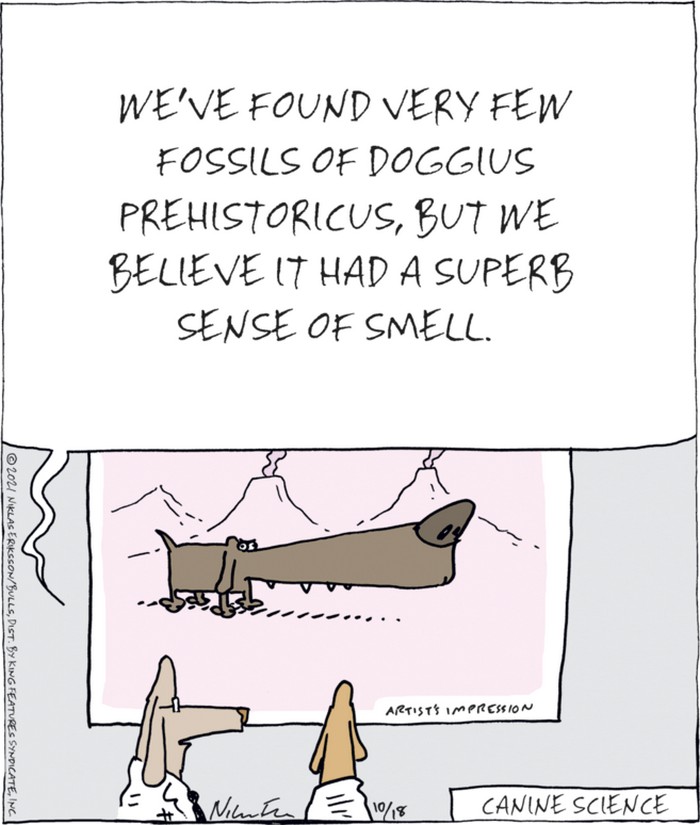

∙Are cats or dogs smarter? Both are domesticated, but is one smarter?

By Paula Schaap

Dog and cat owners make a lot of assumptions about their four-footed companions’ intelligence. Of course, we all like to imagine our Fido or Felix is the smartest animal ever to fetch — or pounce on — a ball. So, can we settle the age-old debate? Which species is smarter: dogs or cats?

Turns out, the answer isn’t as straightforward as pet lovers might like.

“Dog-cognition researchers do not study ‘intelligence’ per se; we look at different aspects of cognition,” Alexandra Horowitz, a senior research fellow who specializes in dog cognition at Barnard College in New York and the author of “Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know” told Live Science.

In fact, Horowitz questions the human habit of comparing intelligence across species.

“At its simplest form, cats are smart at the things cats need to do, and dogs at dog things,” she said. “I don’t think it makes any sense at all to talk about relative ‘smarts’ of species.”

Brian Hare, a professor of evolutionary anthropology at Duke University, agreed with that assessment. “Asking whether a dog is smarter than a cat is like asking whether a hammer is a better tool than a screwdriver — it depends on what it was designed for,” he told Live Science.

This is not to say that animal behavior researchers haven’t tried to measure dog and cat intelligence — or, more precisely, cognitive abilities beyond those needed to sustain life.

Kristyn Vitale, an assistant professor of animal health and behavior at Unity College in Maine, said animal intelligence is typically divided into three broad areas: problem-solving ability, concept formation (the ability to form general concepts from specific concrete experiences) and social intelligence.

Vitale primarily studies cats, and her current focus on the inner life of cats revolves around social intelligence. Often stereotyped as aloof and disinterested in humans, cats actually show a high degree of social intelligence, “often at the same level as dogs,” she told Live Science.

For example, studies show that cats can distinguish between their names and similar-sounding words, and they have been found to prefer human interactions to food, toys and scents. Human attention makes a difference to cats: A 2019 study published in the journal Behavioural Processes found that when a person paid attention to a cat, the cat responded by spending more time with that person.

In one of the rare studies directly comparing cats and dogs, researchers found no significant difference between the species’ ability to find hidden food using cues from a human’s pointing. However, the researchers noted that “cats lacked some components of attention-getting behavior compared with dogs.” (Pet owners who’ve watched a dog beg at its feeding bowl while a cat walked away know exactly what the researchers observed.)

Cats and dogs are intelligent in different ways.

Then, there’s brain size. A commonly held notion is that brain size dictates relative intelligence, and if that were always true, dogs would appear to prevail.

Hare said he and University of Arizona anthropologist Evan MacLean recruited more than 50 researchers around the world to apply a test they developed across 550 animal species, including “birds, apes, monkeys, dogs, lemurs and elephants,” he said.

The idea was to test one cognitive trait, self-control, or what researchers call “inhibitory control,” across species. Their test, reported in a 2014 paper published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, was the animal version of the famous 1972 Stanford University study in which children ages 3 to 5 were tested on their ability to delay eating a marshmallow.

The cross-species study showed that “the bigger the brain an animal had, the more self-control they showed in our animal marshmallow test,” Hare said. The ability to exercise self-control is one of the indications of higher cognitive function.

But there is one catch: Cats weren’t included in the test, so while we can speculate how they might have performed based on their brain size, we don’t actually know.

Another thing to keep in mind when doing this kind of intelligence assessment is that we may treat dogs and cats differently, Vitale said.

So, ultimately, who wins? The takeaway may be to appreciate your pet’s particular kind of intelligence, especially the social intelligence that makes them delightful companions.

∙A new study conducted by Mars Petcare and published in The Veterinary Journal has shown that smaller breeds of dogs, such as Dachshunds and Toy Poodles, are generally more predisposed to periodontal disease than larger breeds, such as German Shepherds and Boxers.

For the study, researchers reviewed more than three million medical records from Banfield Pet Hospital across 60 breeds of dogs in the United States, finding that periodontal disease (both gingivitis and periodontitis) occurred in 18.2% of dogs overall (517,113 cases).

The authors say that while the true prevalence of periodontal disease (44-100% of cases) is only realized through in-depth clinical investigation, the figure reported in this study was consistent with other research based on conscious oral examinations.

When the authors reviewed the data by dog size, they found that extra-small breeds (<6.5 kg/14.3 lbs) were up to five times more likely to be diagnosed with periodontal disease than giant breeds

Additional risk factors for periodontal disease seen in the study included a dog’s age, being overweight and time since last scale and polish.

The five breeds with the highest prevalence of periodontal disease found in the study were the large Greyhound (38.7%), the medium-small Shetland Sheepdog (30.6%), and the extra-small Papillon (29.7%), Toy Poodle (28.9%), and Miniature Poodle (28.2%). Giant breed dogs (such as the Great Dane and Saint Bernard) were among the lowest breed prevalence estimates.

The authors say there are several potential reasons why smaller dogs are more likely to develop dental issues than larger dogs. For example, smaller dogs may have proportionally larger teeth, which can lead to tooth overcrowding and increased build-up of plaque leading to inflammation of gums. Smaller dogs also have less alveolar bone (the bone that contains tooth sockets) compared to their relatively large teeth.